Odds are you know someone living with drug and/or alcohol addiction. But you might not know the personal impacts of the disease. Addiction is not a choice — it’s a disease that changes the brain, and it can happen to anyone. Here are a few stories of the many faces of recovery in our community.

Alcohol was the root of everything. The first time I got drunk, I was 14 years old. By 15, I noticed I was drinking differently than my friends. I was so ready to open that bottle. I just wanted to repeat that feeling again.

Soon, I was drunk every day. I dropped out of high school because it was keeping me from drinking. I found out Listerine had alcohol in it — it didn’t taste good and my stomach would swell, but I couldn’t stop drinking it. I was getting tickets as a Minor in Possession of Alcohol left and right. I was out of control.

I got another ticket when I was 18, and the judge sentenced me to six months in jail. After the first couple of weeks with no access to alcohol, my head cleared. I thought I was cured. I didn’t know anything about addiction.

I stayed away from alcohol after I got out of jail, but I started doing meth — I figured at least I wasn’t drinking. Meth seems great at first. It raises your dopamine levels. You’re super nice, talkative, confident. I was going above and beyond at work. But meth fries your pleasure centers; you can’t find pleasure in the normal things in life anymore. I went from using once a month to weekly to daily. I became paranoid and got fired. At 19 years old, I was living in my car. Everyone I knew did meth, and I stopped spending time with my family. I had no motivation.

Then I relapsed on alcohol. I’d replaced my alcohol addiction with meth. Now I was back to alcohol, and it went absolutely downhill. When I was high on meth, I’d have to drink more to feel it. When I’d get too drunk, I’d do meth to even out. It was an endless cycle. My main goal in life was to stay drunk and high. I was living in bathrooms, under bridges, at drug houses. Addiction just takes the soul out of you. All your mind focuses on is your addiction.

My turning point happened when I got sentenced to Community Corrections. At approximately 3:45 p.m. on December 5, 2017, I did my last line of meth, finished my last bottle of liquor and turned myself in for incarceration. Day by day, my mind started clearing. And then I had a spiritual awakening. I had a sense that maybe, just maybe, I could change my life. And this desire kept growing stronger.

After 90 days, I was going to be put on probation. But I knew I’d just go back to my old life. Instead, I decided to hold myself incarcerated — stay at Community Corrections voluntarily — until I could get into the New Life Program at Harvest Farm in Wellington. It was hard, but it gave me 6 months to contemplate what I was going to do. I came to the conclusion that if AA works for millions of people, there’s got to be something to it. I had a plan.

Once I got to the farm, I did everything to the best of my ability — working, going to AA meetings, doing the steps, attending church. I was following the rules for the first time in my life. It felt good, and I started getting ambition. I applied for a job at Fort Collins restaurant Ginger and Baker, and I was hired on the spot. I became involved at Genesis Project, a Fort Collins church focused on new beginnings. There, my chaplain encouraged me to tell my story at schools. Now I have a fire in my heart for helping kids. I speak at as many schools as I can and volunteer at the Youth Ministry every week.

There’s a Bible verse that says, “In all things, God works for the good of those who love him.” I use all the bad situations that happened to me for nothing but good now. I love telling my story because it makes me remember where I came from. I’m really blessed to be able to share my experiences and help people.

My addiction blossomed when I was 22. I come from a long line of alcoholics, so drinking was always a normal thing. It was never MY thing though. But when I first tried methamphetamine, it felt like all the weight was lifted off my life and I had found the missing piece. Emotionally and physically, I felt like I could take on the world.

Right away, I was using all the time. In a few short weeks, I went from smoking meth to injecting it, then smoking heroin to IV use. Soon enough, I was using anything I could to get high. It happened so fast and I found that I just didn’t want it to stop. I used for three or four years, but all the things that happened in those few years make it seem like a lifetime.

I regret using heroin more than anything because of all the terrible things I did when I was on it. And because I overdosed on heroin and died — I was legally dead for two minutes before the paramedics were able to revive me. I woke up in the hospital two days later and thought, “What have I done?” That’s when I started to think about my family, my kids, anyone I ever cared about in my whole life. I couldn’t imagine them getting that phone call saying I was dead from an overdose that was 100% preventable.

That started my recovery journey from heroin and meth, and I stopped using for a while. It wasn’t until my ex-husband went to jail that I started using meth again, because I had nothing else to do with my life. I was living in Denver and started using crack. It wasn’t heroin, so that’s how I justified it to myself.

Then I got arrested — again. At that point, I had open cases in six counties. After a month in the Denver jail, I was moved to the Larimer County jail for a 7-month stay. During those 7 months, I made my rounds to all the other counties to finally get closure on my old life. From there, I went to Community Corrections, the halfway house, for 18 months of treatment. Within the first month, I found out my now ex-husband was cheating on me, my oldest daughter’s dad was moving her to Montana and my youngest daughter’s dad had no plans to let me see her until I was out of the halfway house. Every reason I had to stay sober was gone.

I dealt with it the only way I knew how. I got high. When my next substance test came back with trace elements of drugs, I was put into the IRT (Inpatient Residential Treatment) program, which is 40-48 hours of intensive treatment a week. It was like a full-time job for my emotions and all the things that I tried to run away from when I was using. I hated it at first and fought it every step of the way, but the Community Corrections staff and my therapists worked with me. They really wanted me there and wanted me to complete the program. I’d never had people support me so strongly before in my recovery.

So I put all my energy into IRT. I stopped making excuses and settling for less. Even when it was hard, I never thought, “I’m going to get high to solve this problem.” That had been my solution for so long. If I wanted things to be different, I had to DO things differently.

I started taking action. In jail, I learned that running was a good way to burn off energy and keep my emotions in check, so I helped establish a running club at Community Corrections. It started with one of the staff taking notice of the commitment from myself and a couple of the other women. She approached us about participating in a race in the community; this was unheard of at the time, to go out into the world during treatment for something that wasn’t scheduled rec time. She made it happen for us, and it became a big part of our recovery. Experiencing that camaraderie, encouragement and empowerment — knowing that you’re going to finish a race with your team — it’s cool. The running club opened doors for us and has opened doors for a lot of people since.

That staff and I went on to found a nonprofit, Strength Through Connection, to expand our work into the community at large. Through running and teambuilding, we empower ourselves and others, build relationships, give back with volunteer work and help erase the stigma around addiction.

We also started a Northern Colorado chapter of The Phoenix, a national organization that helps people who have suffered from addiction heal and rebuild their lives. We meet at W.I.L.D. Horizons CrossFit every Thursday night, and we have a lot of people on board who are passionate about recovery. We are a family there.

In my recovery, I have found a strong sense of purpose. I know what I’m doing with my life, and I’m genuinely happy. I met my husband in our advanced recovery group at SummitStone, and we work on our recovery together every single day. We are both Sober Coaches for The Phoenix and we are always working with community to build new partnerships to help others find strength in their recovery. Our daughter just turned 1, I have parenting time with my 7-year-old daughter again and I am rebuilding my relationship with my oldest daughter in Montana. I’m happy with my job, with the things I’m doing and where I’m going. I wake up proud of myself every single day. And I know I was never happy like this when I was getting high.

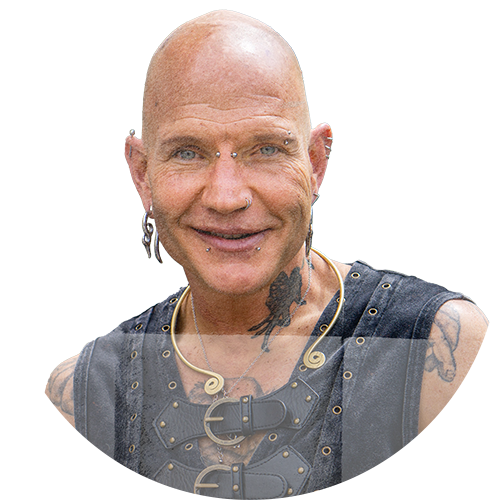

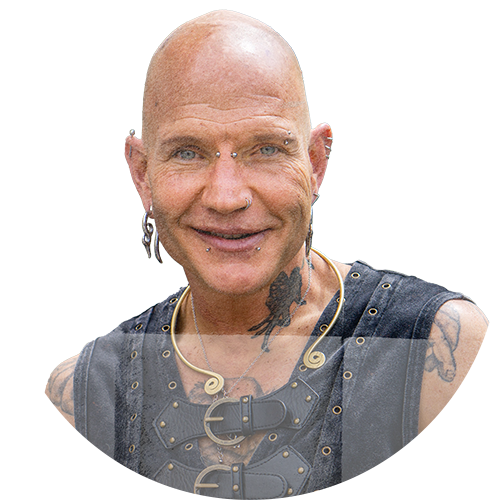

Starting from six years old, I couldn’t understand why I was so ugly and different from all the other children. That was my identification from earliest memory, that I was some sort of hideous monster — never fitting in, never feeling like I belonged, no ability to feel loved. I found food addiction first and compulsive exercising because of my body dysmorphia and self-hatred. Then the drinking started.

My father was an alcoholic. We had a whole separate fridge with a keg in it. I used to steal drinks as a child; they caught me with my head under the keg faucet, which seemed funny to everyone at the time.

At 13, I had my first real drink: three-quarters of a bottle of whiskey with some friends. They kept saying, “Slow down, Rowdy. Slow down!” I think I heard those words for the rest of my drinking career. A lot of people who have an addiction story say it starts out fun and then becomes a problem. Not for me. My obsession from that first drink was: the more I drank and the faster I drank, the quicker I escaped. I hated the world, and I wanted out. That’s what alcohol did for me — took me to the point of oblivion.

I drank more and more. If I wasn’t drinking, I was obsessed with when I was going to drink, when I could escape again from the torment I was living in. I would vomit before I drank to get drunk quicker. Then I’d throw up again after drinking for a while so I could make room for more. The body can only process so much alcohol, but I would drink until I literally couldn’t anymore. I would either run out of alcohol or pass out.

I did things I regretted constantly when I was under the influence. I was a liar and a thief, not a nice man. But alcohol was my solution. There’s a great line in the Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) Big Book: “I commenced to forge the weapon that one day would turn in its flight like a boomerang and all but cut me to ribbons.” Drinking was the weapon I forged to deal with life. It was the only tool I had. Unless I was drunk, I was miserable. But the drinking was tearing me to shreds.

At age 20, I went into inpatient treatment. They told me, “You’re not crazy, you’re an alcoholic.” That gave me some hope, so I completed treatment and started going to AA meetings. I followed the program, but I was still depressed and suicidal. I saw how AA was changing lives, but it wasn’t helping me. That was when I went from ideation to decision; I decided I was too broken to be fixed and the world would be better off without me. I was later diagnosed with seven different DSM-5 codes for mental health disorders, but I didn’t know it at the time.

So when I went back to drinking, it was a suicide attempt. But it didn’t kill me. I tried again — took an enormous amount of psychotropic medications and then taped a plastic bag around my head. I would have succeeded, but my roommate came home and found me. I was rushed to the ER and landed in the psych ward with alcohol-induced psychosis. It was not pretty. I was just sitting in the day room rocking back and forth in my chair, completely shut down. I had no feelings, just that rocking. Eventually, I was put in a dual diagnosis program for mental illness and substance use. I got out and went back to AA.

Then, for seven and a half years, I did the work in AA. I was still suffering from crushing depression, but I kept at it anyway. At the end of those years, I realized that even though I was miserable, I was still being of service by sitting in those chairs and showing people that you can stay sober, no matter what. I chose to live, even if life wasn’t ever going to get better, because I was helping others despite my torment. That realization was the breakthrough I had been waiting for.

Looking back, I realized I had been making friends, I just didn’t know I had been connecting. I’d never known connection in my life, never felt it. I had also learned how to stay sober through adversity. I’m now at 29 years sober, but I never take my sobriety for granted. I’m still doing the work like my life depends on it.

The debt that I owe for having my life back, I repay in service. I do an enormous amount of work within AA. People are constantly coming to me. That’s the gift of having all these DSM-5 codes — having issues that I used to think were so unfair — now I can help. When I’m working with someone struggling with addiction or suicidal thoughts, I can say the magic words, “I know how you feel.” Chronic mental illness, chronic pain, disabilities, trauma … I truly understand, and I can help.

I tell people, I wish I could put you in my head 29 years ago, rocking in that mental hospital, and then put you in my head today — there are no words to describe the change. I still have issues, but now I identify myself as beauty beyond belief, but covered with scars. The scars make me who I am and help me help others.

I also volunteer for Imagine Zero, which partners with the Alliance for Suicide Prevention of Larimer County. I’ve spent 27 years working with intellectually and developmentally disabled adults. And I’m on the Larimer County Dive Rescue Team.

I went back to school and am now finishing up my master’s degree in social work. I’m passionate about so many different at-risk populations. After I get my degree, I’ll likely find a place like an acute treatment center where I can work with a variety of traumas. Whatever I do, I know it’ll be helping others. My life’s purpose is to be of service and pay back the gift I was given. The sky’s the limit.

When she was in eighth grade, my younger daughter Taylor started taking cold pills to get high with her friends. She ended up in the emergency room several times. I got her into counseling with good results initially, but when she started high school, she began using other drugs.

In the meantime, my older daughter Brittany was living in Iowa and having troubles of her own. She was caught using drugs multiple times and was eventually sentenced to a rehab facility. It was a family rehab, so at least she could go with her son. But as a mom and grandma, it was heart-wrenching to leave them there.

Both my girls were struggling with addiction, and I was trying to help them across two states. At the time, I was laser-focused on Taylor, not worried about Brittany. Britt was always my go-getter, and very goal-oriented. I thought she would just stop.

After 30 days in the rehab facility, Britt failed a drug test. She was kicked out, and her son was put into foster care. I thought Brittany was at rock bottom. I couldn’t understand why she couldn’t do what was being asked of her – to stop using. I grew up thinking that you just go to rehab and everything will be fine. I didn’t know enough about addiction, even though I had experienced it myself when I was younger.

Methamphetamine was my drug of choice. I used off and on for seven years, but I didn’t feel I ever developed an intense physical addiction. I never felt like the drug life was the life for me. Eventually, I was able to just stop. I moved to a new state and changed my lifestyle. I embraced my life in recovery, and I still do.

Brittany was addicted to heroin and seemed to get a rush out of the lifestyle, though. She became enmeshed in it. She was in and out of outpatient treatment, trying to do what they wanted her to do — and then failing. Eventually, a judge terminated her parental rights, and my husband and I adopted our grandson. I can’t imagine how that felt to Brittany, to lose that part of her identity. Being a mom was everything to her.

Meanwhile, Taylor was using meth and spiraling out of control. She was pulling out her hair, hallucinating, talking to herself, overdosing — she was in the ER 10 times in 2014. I felt like such a failure as a mother. I kept trying to get Taylor into an inpatient rehab but was always given an excuse. I was told I didn’t have the right kind of insurance, or there weren’t any beds available. I was so afraid she was going to die that I turned to the TV show The Extractors. In exchange for sharing our story, the intervention team would get my girl some help.

Taylor was 78 pounds when the Extractors showed up. They swooped in, took my child to rehab and she was gone for nine months. When they realized Brittany was also suffering from addiction, they offered her the chance to go to rehab as well. She was offered a 90-day stay at an inpatient facility.

That was the first time in years I’d been able to breathe, sleep, and think about what I wanted to do with my life. When we went to visit Taylor during rehab, we met her therapist — I thought, I want to do THAT. In the summer of 2016, I started working on my master’s degree in mental health counseling from the University of Northern Colorado.

In June 2015, the very day Brittany got home from rehab, she went out to see friends and started the cycle again. Taylor came back four months later and lasted three weeks before she started using again. I was heartbroken.

Things turned around for Taylor. She met her now-husband Jon. Both had drug use in common, but Jon was different. He had goals. He wanted a job, a house, a family. They found each other at the right time and fought to enter recovery together. Once Taylor had somebody to support and love her, life became a different story.

Brittany, on the other hand, started getting into more legal trouble. I let her stay at my house — I continued to think that my love would fix this. I couldn’t live with the thought of her being on the streets or dying somewhere alone. I was so ill-informed about opioids and heroin then. The times I thought she was high, when she wouldn’t get out of bed for days, she was actually withdrawing. When she was up and moving, it was because she had gotten “well” with heroin. She wasn’t using to get high. She was using to function.

In December 2016, after a 20-day stay in jail, trying to break her addiction and suffering through the worst withdrawal symptoms of her life, Brittany came home and overdosed — 28 hours after her release. My husband and I found her in the bathtub, dead. It was the most devastating moment of my life. Eventually we learned it was fentanyl that killed her. For six months, I floated through life, trying to be there for my grandson. I almost gave up on school and my dream to help others suffering from addiction.

I’ve learned so much in the past few years. Maybe some of the resources I know about now would have been an option for Brittany, like medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which helps people detox without going through so much sickness and pain like Britt did. I don’t think we should expect people to withdraw in an inhumane manner. I don’t think that’s too much to ask of our medical, rehabilitation or correctional facilities.

I graduated last year and got a job at the Boulder County Jail as an Opioid Behavioral Health Reentry Coordinator. Our team screens people upon arrival and provides those who need help with a resource list they can use when they leave. But it’s more than a list. It’s a face-to-face connection, a way of saying, “Hey, somebody cares.” I care. Our team cares. We provide support for those who remain in the jail. My goal during every interaction is to put a positive face on counseling. If clients have been intimidated by an experience in the past, maybe they’ll think, “That lady wasn’t so bad. I’m going to look into another counseling center.” Through it all, everything I do is to honor Brittany, in addition to Taylor, who currently has over 4 years in recovery.

My dad is a retired Denver narcotics detective, so drugs were not an option growing up. I tried cocaine when I was 18, and it was all right. Nothing special. I didn’t come back to drugs again until I was in my 40s. But addiction can happen to anyone at any time.

I was very successful from age 19 to 45 in the auto industry. I made a great living, had a great career. Then one night, I succumbed to trying cocaine again. This time, it was crack. From that point on, I was the poster child for “Why not just try it one time?”

Crack is an instant high, a dopamine overload. You go up really quick but come down even harder. The craving for more is what got me. I committed crimes and stole from family and friends because I had to have that drug. I couldn’t stop. Within months, I lost everything: my marriage, my house, my career, everything.

The first time I went to rehab, it was for 30 days. I got out and relapsed within 45 minutes. My dad said, “What do you mean, you relapsed? You just got done with rehab.” Like this magic wand was waved over my head. My family was very supportive, but they didn’t understand addiction. They did their due diligence researching crack cocaine and finally did enough research to realize they were enabling me, not helping me. So they put their feet in the ground and said, “We’re done.” I’ll never forget my mom telling me, “We’re going here, you’re going there, and we’re not going to meet in the middle. You either have to come back here, or adios. We don’t condone what you’re doing.”

I reached out to a friend who worked for the Denver Rescue Mission, told him I needed help and got in their system, but it was a struggle. People right outside the door were using drugs.

I heard about Harvest Farm in Wellington and enrolled in their program. I stayed for 15 months, graduated and was doing great. But then I stopped doing what I learned in treatment: going to meetings, calling my sponsor, going to church. I stopped doing everything that got me the 15 months of sobriety and relapsed.

Soon after, I landed in Larimer County Adult Drug Court. That whole program changed my life. It taught me accountability. It taught me you’re going to do what you say you’re going to do. It taught me immediate gratification or immediate consequence — you’re free to choose, but you’re not free of the consequences of your choice. And it taught me to put recovery first.

After graduating from Drug Court, a position opened up at Harvest Farm, and I got the job. I’ve been here for about five years now and have risen through the ranks. I’m a supervisor now, have obtained my Certified Addiction Counselor level one certification (CAC1), am almost done with my CAC2 and am a certified Peer Support Specialist. I have dedicated my life to helping the guys here find the freedom I found in recovery.

Recovery is number one. Nothing else gets a number. I learned that from the Drug Court therapist Dan Bennett, who became my mentor, and I’ve lived by it as my motto. It works for me. When I share it with the guys at the Farm, they say, “What about God? What about our families? What about …?” I tell them without recovery, you’re not going to have any of the rest. Recovery needs to be number one in your life.

It doesn’t matter how long you’re clean and sober. Addiction is a forever thing. I tell the guys that addiction is like diabetes. It’s never going away. You just need to treat it. If Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA) isn’t your thing — and it’s not for everybody — you better find a support network. Because it’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when you’re going to want to go back to drugs.

Addiction feels like a weight on your back. Acceptance and accountability are the messages I try to convey to these guys. When you can accept the fact that addiction is not going away and are brutally honest and accountable to yourself, you can carry the weight. You understand there are options, that recovery is possible and sustainable.

I helped develop programs at Harvest Farm for the evenings and weekends, when guys used to just sit around. That’s when their heads started going to bad places because they had nothing to do. So we brought in more activities: AA meetings, NA meetings, Bible studies, outings. Not to keep people entertained, but to help them with recovery, show them different recovery tools and community opportunities. This line of work is very rewarding. We graduated 53 guys last year.

I also volunteer for the Mental Health and Substance Use Alliance, and I want to get involved with any board I can. I want to share my story, I want to share my success, I want to give accolades to the people who were there for me. Whatever I can do to help send the message that there is hope.

Addiction was rampant on both sides of my family. I saw substances used and abused regularly, and I started using alcohol and marijuana in junior high. By high school, I was using all the recreational drugs: cocaine, ecstasy, the so-called party drugs. Then I got into opiates as a way to get out of pain from the weekend. Once I became dependent on them physically, I couldn’t get out of bed without them. I couldn’t even think straight. At age 21, I moved to heroin. Even then, I didn’t think I was addicted. I wasn’t homeless, didn’t lose my license, was keeping my life together.

A year later, things were falling apart. I couldn’t hold down a job and had to move back in with my mom. I was 90 pounds soaking wet — only then did it become obvious to me that something was wrong. I turned to my family, and we started trying to get help. Private rehab was never an option, and we were having trouble finding treatment.

Then I got pulled over by the police. I had four different substances on me and was arrested — it completely changed my life. I asked for help and entered the Larimer County Adult Drug Court program, which had the structure and resources I needed. I did 18 hours a week of recovery work: medication, groups, 12-Step, individual therapy and Drug Court therapy. My brain and body needed time to heal. It’s just like any physical injury — when you break your leg, it takes more than a few days to fix.

During treatment, you’re healing physically, mentally, emotionally and psychologically, all while doing what “normal” people are doing — working, taking care of children, keeping up the house. I still spend 10 or more hours a week doing recovery. But I am very grateful that I’m alive and I get to do that. I graduated from the Drug Court program, and I helped start a nonprofit that directly benefits clients who are in the system like I was — helping people however we can to help them succeed. Being in recovery gives me a chance to show people what’s possible. I volunteer my time and share my story every day. I want people to understand the reality of addiction and not false beliefs, to educate the upcoming generation so change can start to happen and life overall as a community can get better.

On my 18th birthday, I bought a six-pack of beer. As I cracked open the second one, all of a sudden this wash of wonderfulness came over me that I now know was a dopamine rush. My switch was flipped. Right off the bat, I started into heavy drinking. But there weren’t really any consequences. I got a DUI, a little slap on the wrist in college. Then off to medical school I went. I did well — graduating near the top of the class — but alcohol was already starting to take over.

I got into my professional life and started using drinking as a tool to help me sleep after a big shift. Instead of a fun reward, alcohol became a coping mechanism. I was an ER doctor at the time and had taken care of hundreds, if not thousands, of people with addiction by that point. You see the fallout of addiction nowhere more than in the Emergency Department. But even when I went to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting as part of a residency requirement, I didn’t identify with it.

By the time I realized I ought to limit my drinking, my marriage was in shambles. But I was a doctor — who could I ask for help? Shame and guilt and ego all came into play. Even though I knew about the effects of addiction on the brain, I couldn’t internalize it. Finally, my wife left me, and I thought, “That does it.” I went through detox, started going to AA meetings and started feeling better.

Ten months later, I was at a neighborhood party and grabbed a margarita to celebrate my divorce being finalized. Guess where I went after the party? The liquor store. And then there I was, in the loop again, after not drinking for 10 months. I went into a 2 and a half-year relapse that I couldn’t escape — I was stuck around the bottle 24/7, most of the time wishing for death.

I lived like that until my family and friends staged an intervention. Off I went to a residential treatment program, believing it was my last chance at recovery. After 60 days, I realized the treatment wasn’t about not drinking — that was done. If I never picked up a bottle, that wouldn’t happen again. Instead, everything I’d done was about building balance within myself and having the best possible relationships and life I can have.

Ever since then, I’ve never looked back. It’s not bad or good that I have an addiction. It’s just a fact. Instead of “I can’t drink” — I know I can. And I know exactly what will happen if I do. So I can drink, I just don’t want to. If a human being gets their mind set about something they don’t want to do, you can’t make them.

I’m on year six of not drinking now. I experience joy on an all-day, every-day basis. I go to meetings regularly, I have a sponsor and I have a ton of sponsees. I care for patients suffering from addiction for a living. And I cannot believe how lucky I am.

Addiction has been part of my life since the day I was born. Both my parents suffered from drug and alcohol addiction. I went into foster care at age four because we were six kids and two parents living in a station wagon. In high school, I drank beer and wine coolers and partied with my friends. As I got older, I would buy beer on my lunch break and leave it at home; that way I’d be sure it would be there after work. I’d hurry home so I could drink it, and then I’d drink until I passed out. I was productive, but I had an addiction.

Then one night I tried meth. One hit and I was hooked. That was it. Everybody uses the word euphoria to explain how it feels to be using meth. You don’t have common sense, but in your eyes, everything is perfect. You lose your inhibitions; everything seems so fun. Except you’re not in control. You think you are, you tell yourself you are, you tell everybody else you are. But you’re not. Nobody experiencing an addiction thinks for themselves.

Even after I watched my boys getting taken away — watched them being driven off and waving from the back window just like in the movies — I didn’t think I had an addiction until I started treatment through Family Treatment Court. Once the cloud began to lift, I could start to see clearly. Three months in, I realized: wow, I’m changing my life. Treatment is a lot of work, but it’s worth it.

Recovery has changed me as a person. I’m a better dad, fiancée, employee, human being. Everything has completely turned around. I have control now, not pretend control. I make choices and it’s all me. Whatever happens, I can handle it. Things just keep getting better and better because I keep making good choices.

The biggest part of my therapy is that I can help other people. I can contribute a lot to a room full of people by sharing my story. As part of the Larimer County Trauma Team, I help families that have been separated get through the system — I mentor them and watch them graduate. It’s so rewarding, one of the best things in the world.